Bitsii moved to a remote fishing town in Ehime prefecture in 2021. She wasn’t ready to commit anything major since she was new to Japan and unsure visa renewal potential — until the locals handed her first vacant akiya house.

This interview with Bitsii is full of interesting insights about akiya DIY and living in rural Japan.

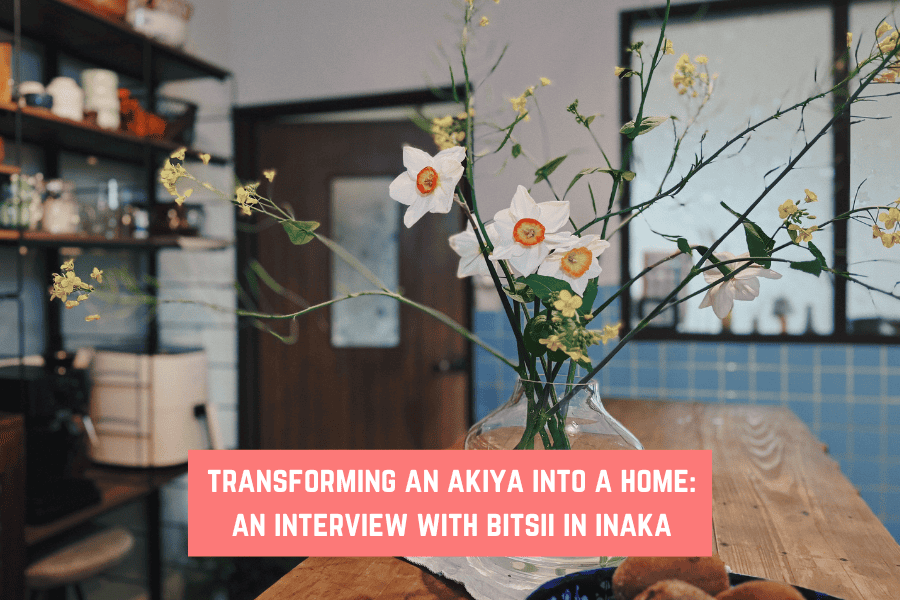

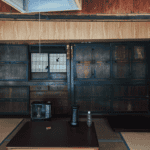

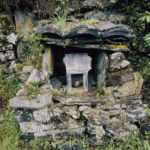

*All the photos on this page are of the house and property where Bitsii lives..

Would you mind quickly introducing yourself to our readers? How long have you lived in Japan and what brought you there originally?

“When I arrived in Japan and stepped into my first akiya (vacant house), I felt an immediate connection for several reasons.

The house was elegantly simple and made honest use of materials.”

Where is your house? Why did you choose that location?

Bitsii: I initially moved to a remote fishing town in Ehime prefecture on Shikoku island. My work assignment brought me there – I had never heard of Ehime before. While I’ve always had a passion for houses, I was new to Japan. Unsure about my visa renewal potential, I was not ready to commit to anything major. However, the locals handed me my first vacant akiya house, and together we worked out an arrangement where I could help renovate it while figuring out my long-term plans. Essentially, I didn’t choose the location or the house; they chose me.

Eventually, I met my now-husband, Koichi. He’s a Tokyo-born former Kyoto gardener who shares my interests in DIY projects, sustainable living, gardening, design, and creative projects. Koichi was involved in a rural revitalization project based in Ozu, Ehime, often referred to as “Little Kyoto.” We decided to get married and collaborate on projects together. Koichi was also taking care of an akiya in a small mountain town with kiwi orchards as part of his work. Since his orchard agreements were integral to his work contracts and my work was temporary, it made sense for me to join him in the mountains.

“… the locals handed me my first vacant akiya house, and together we worked out an arrangement where I could help renovate it while figuring out my long-term plans.“

What do you like best about living in rural Japan? Were there any surprises or challenges that came up?

Bitsii: One of the main reasons I like rural Japan is its natural beauty. Japan has diverse landscapes, including mountains, hot springs, ocean vistas, volcanoes, and rock terraces. Our eating habits are deeply intertwined with the seasons and local agriculture. Even those not directly involved in farming often tend to their own hatake (vegetable garden plots). In our area, we have numerous beekeepers, kiwi and mikan (mandarin orange) orchards, chestnuts, plums trees, and more. Additionally, there’s an abundance of wild seasonal vegetables to forage, such as takenoko (bamboo sprouts) and tsukushi (horsetail sprouts).

Foreign residents are rare in rural Japan, and even fewer fully integrate into their local communities or share their experiences. Therefore, it’s natural that life in rural Japan presents numerous surprises and challenges. Perhaps the most significant surprises and challenges stem from the social and labor-related expectations rooted in these close-knit communities. These expectations often rely on order via seniority, resembling a clan mentality that can be challenging for both non-local Japanese residents and international people to navigate.

Approximately how much did you purchase your house for? Were there any unexpected costs?

Bitsii: My first akiya was offered to me to buy for zero yen, with additional taxes and fees to be paid. I started staying there on a trial basis and paid 10,000 yen per month to a Japanese intermediary who had contact with the legal inheritor of the home. He also managed a construction business and assisted with some maintenance tasks, such as fixing frozen pipes and repairing the bathroom roof after a typhoon. I have a detailed breakdown of monthly expenses from that time here.

In our current home, my husband and I live rent-free. There is a possibility of ownership in the future. We reside here with two houses on the property—a concrete construction primary residence and a 100-year-old wooden kominka. While our landlord covers maintenance costs, we plan to increase our rent voluntarily as our businesses grow, out of respect for her generosity.

I was aware of potential termite damage and the need for costly roof replacements in both houses. However, I was surprised by the local mindset regarding these issues, which tends to be a “if it’s not a problem now, it’s not a problem” attitude. Anticipating and budgeting for future expenses has been challenging in rural culture because people don’t like to talk about money. On the positive side, this aversion to money makes it less likely to be exploited financially. Here, prioritizing non-monetary virtues is highly regarded. As someone seeking an intentional lifestyle, I love this. But I’ve spent all of my life focused on optimizing budgets, setting timelines, defining contingency plans, and anticipating expensive maintenance. Here in this remote village, those topics aren’t seen as responsible. They are seen as cold, insensitive and distasteful. That’s a challenging gap to span.

“Here, prioritizing non-monetary virtues is highly regarded. As someone seeking an intentional lifestyle, I love this.”

What renovations did you do? How long did the whole renovation process take and how much did it cost? Were there any unexpected costs?

Bitsii: Thankfully, my first house was in good condition overall. It required a new electrical panel and a control panel for the hot water heater, totaling around $800 USD. I also replaced two leaky faucets and did a thorough cleaning. I approached the project with care, consciously sorting through all the items left behind as a gesture of respect for the previous resident and the local community. Among the treasures were old school photos, family memorabilia, beautiful kimono fabrics, an ikebana degree, a variety of dishes, and an unnecessarily generous quantity of futons. Organizing everything took several weeks’ worth of evenings and weekends.

In our current home, renovations are progressing slowly due to multiple parties involved. Our landlord, having grown up here, is emotionally invested in preserving the kominka. I’ve made updates to the newer concrete house. I’ve now put about $300 into a DIY overhaul of our kitchen. There, I refinished and repurposed old Japanese tansu into cabinets. Larger expenses are anticipated for the kominka. Potential costs include $3000 for termite services and up to $50,000 for a new roof, though decisions regarding these improvements have yet to be finalized and we will not bear the majority of the cost ourselves.

“I approached the project with care, consciously sorting through all the items left behind as a gesture of respect for the previous resident and the local community.“

What advice would you give to someone who dreams of living in the Japanese countryside?

Bitsii: My top advice would be to learn Japanese as best you can before moving to rural Japan. While it might seem like a significant undertaking, it’s essential for navigating daily life here. Initially, I thought immersion would be the most effective way to learn the language. I’ve realized that, being in my thirties, immersion is better for reinforcing knowledge rather than it is for first-exposure learning.

And moving here didn’t magically create more time for language study in my schedule. In fact, living in rural Japan means everything takes longer, leaving less time for learning Japanese. Instead, I’ve found myself grappling with increased paperwork and challenging translations during everyday tasks. It’s best to learn the language beforehand; there will be plenty of other things that will demand your time.

Anything else that you’d like to share with Cheap Houses Japan readers?

Bitsii: CHJ followers see the value in Japanese houses – sustainability, beautiful culture and tradition, natural lifestyle, and financial freedom. As an interior designer, I’ve been collecting home resources for those who manage to make their way into houses here. This includes inspiration, DIY, furniture shopping resources, information about home appliances, traditional materials, home maintenance tips, and the like. Everything from mold and bug control to the best online vintage furniture stores. Navigating Japanese internet can be a mess if you are less than fluent. So for those looking to get settled in a Japanese house, we are in the process of building inakahouse.com with J-centric sources. We want to empower international people with everything they need to turn a house into a wonderful home in Japan. It can be a lot to manage (I know! I’ve been there!), so I felt compelled to share what I’ve learned so far.

Bethany's House Photo Gallery

A big thank you to Bethany for sharing her story here. What do you think? Would you to have a house like hers in Ehime?

If you need inspiration to find your dream vacation house in Japan, follow Cheap Houses Japan on Instagram.

Looking for more advice about buying a house in Japan? Read this article I wrote: